Imagine losing a parent, having parents that cannot care for you anymore, or being taken away from your abusive home. Later, you arrive at a complete stranger’s house, which is now where you live. This is the reality of 400,000 foster children in the US. The system is intended to provide structure and stability to the extremely vulnerable children who enter it. However, the foster care system has provided anything but stability for some, and flagrant exploitation of the system is all too common.

Several students at Central Hardin have either been in foster care or are currently receiving non-kinship care: the two interviewed in this article are Meadow Simpson, a senior who is getting adopted, and an anonymous student. For her safety, she is given the pseudonym Jane Smith.

Smith has been in the foster care system since she was 6 or 7, floating around from one house to another like a ship lost at sea. Instead of a permanent, supportive pair of role models, her countless caretakers have been more like bosses than parents.

“I was in foster care and then out of foster care and then in foster care,” Smith said. “It can be really scary.”

Similarly, Simpson constantly worried about her next home. While she was in respite care, her foster parents warned her that she could be put in an abusive foster home at random. She never knew whether her next home would truly love her or have ulterior motives. One of her caretakers even said, “I can’t promise that we can keep you safe [from other foster homes].”

“In respite care, you never know where you’re gonna go,” Simpson said.

Both Simpson and Smith have been at some foster homes for an extremely short period of time, which meant they barely got to find a group of friends at their schools.

“The most challenging part of being in foster care is having to move from place to place and having to make friends all over again,” Smith said.

The stigma around foster care also affects foster kids’ ability to find belonging. Simpson finds that people give her unnecessary pity when they find out that she is in foster care. She does not want people to patronize her by making her suffering seem insurmountable. She just wants to look forward to the positive things in her life.

“Whenever I tell people that I’m in foster care, they’ll start to pity me. I don’t need pity,” Simpson said. “It’s people who are less fortunate in foster care that you need to take pity on.”

Furthermore, many well-meaning people assume Simpson’s situation was fraught with severe abuse and neglect, but she says that was simply not the case. She has actually maintained a good relationship with her biological family.

“My dad still loves me,” she said.

There is also a stereotype that foster children are extremely disobedient. As Smith was conversing with a student at a new school, the student told her, “You don’t act like everybody else in foster care.”

Society’s low expectations for foster children may contribute to many of them having low expectations for themselves.

Only 50% of foster care children finish high school. Additionally, only about 4% of foster children obtain a four year degree. These heartbreaking statistics prove that the American education system is failing those who have nowhere to call home.

“I wish people knew that it isn’t easy to not bring your home life to school.”

— an anonymous student in foster care

Some schools are failing to provide adequate education as well as mental health accommodations. Smith sometimes has panic attacks during school because of her social anxiety. She was once enrolled at a private school, and when she had a panic attack one day, the teacher did not allow her to step out of class to calm down.

Coping skills are paramount for foster kids like Smith. According to Youth.Gov, children in the foster care system are almost four times as likely to attempt suicide. According to the CHKS, foster kids are twice as likely to abuse substances.

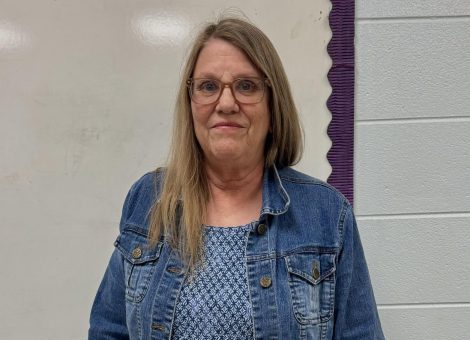

2022 Central Hardin graduate Kenzie Stambaugh, a former behavioral health technician who currently works at a daycare, said that these statistics could change if the government was more scrutinous of the foster parents.

Stambaugh said that “not all parents do it for the sake of the kids.” Foster parents are given stipends to take care of the children, but those subsidies may have the unintended effect of drawing the wrong people to the system.

“A lot of teenagers I received at the hospital said, ‘I don’t think my parents want me.’”

“It feels like I never really left home. It feels like I’m still with my family.”

— Meadow Simpson

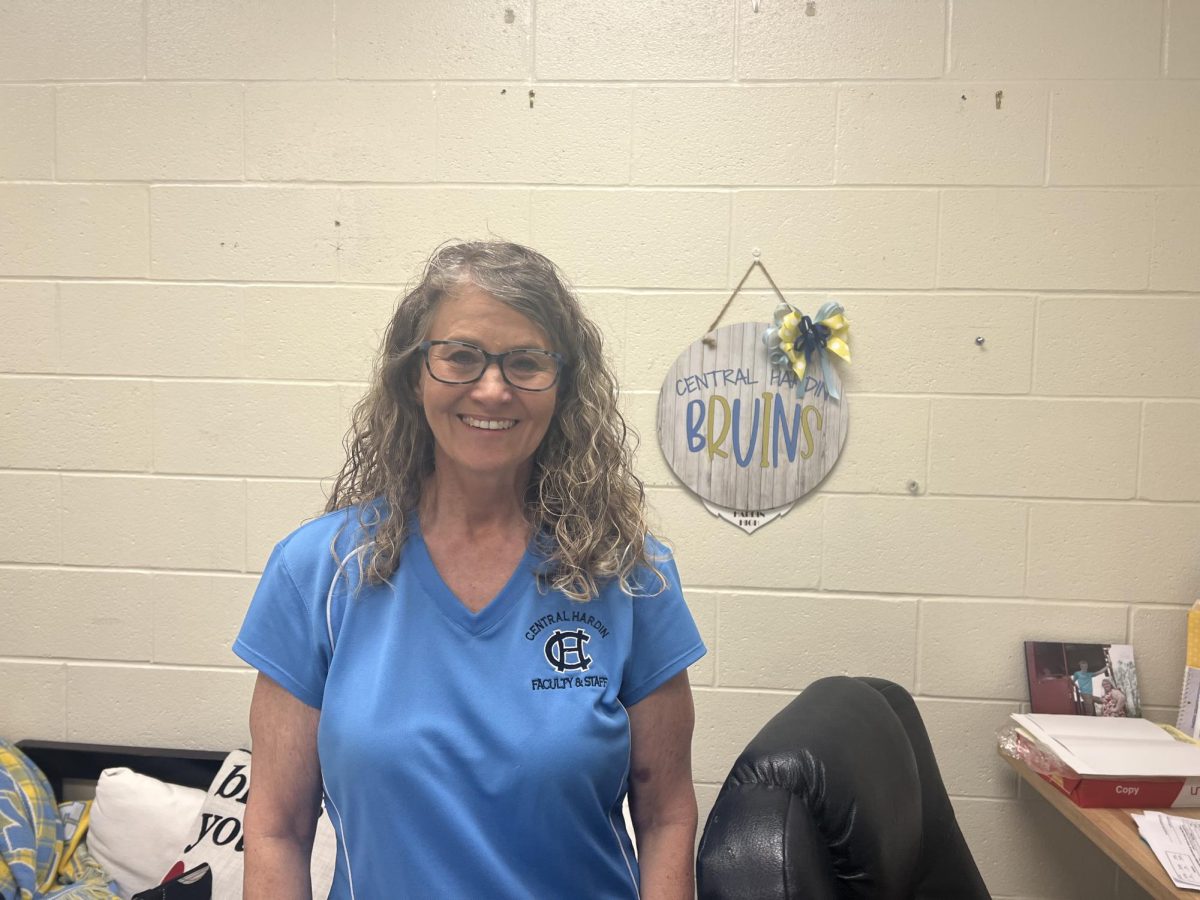

The foster care system is in desperate need of reform, but it is important to remember that generalizing every child’s foster care experience is also unhelpful. Simpson, who has lived in four different homes, has finally found a place she can call home for the rest of her life. She spent many of her years moving around the state, but at the end of her sophomore year, the Tingle family took her in. She will be adopted on Feb. 13.

“It feels like I never really left home. It feels like I’m still with my family,” Simpson said.

Simpson is a reminder that there is a light at the end of the tunnel for all who are brave enough to keep going. Any foster child in your life may need extra support because of their extenuating circumstances, especially with the poor design of our government’s current foster care structure. Ultimately, it is up to our lawmakers to mend the broken system.

“No child deserves to feel like they’re not loved,” Stambaugh said.